[In this series, we interview hosts for Slow Art Day and get their thoughts on hosting, the art of looking, and the slow art community. Today we interview Elizabeth Markevitch, who is a global sponsor of Slow Art Day through her interesting company, ikonoTV, Berlin.]

Slow Art Day: Let’s start with a bit of background about yourself and ikonoTV. You are the founder, right?

Elizabeth: Yes, I founded ikono in 2006.

Slow Art Day: What was your founding vision?

Elizabeth: During my long-time experience in the art world, I became more and more aware of the necessity for exploring new ways of displaying art and opening it up to a broader audience. Art needs to be seen, and the joy of seeing and experiencing art should not be restricted to a small group of art professionals or collectors.

Slow Art Day: As you know, of course, we share that vision with you. How did you get from that vision to starting ikono?

Elizabeth: I explored different paths. I cofounded www.eyestorm.com in 1998 as the first online gallery at that time selling international contemporary art on a global scale. Then, some years later, the fundamental idea of making art internationally accessible found its final and strongest realization through ikono.

Slow Art Day: So why bring art to TV in this new way?

Elizabeth: I thought why not achieve for the arts with TV as radio has been achieving for music? Why not use this mass medium for bringing the entire world of arts into the homes of an international public? Over the past few years, we have established a wonderful collaboration between art historians, curators, and cameramen in working with artists and international art institutions. We are producing video clips about artworks from all time periods, movements and disciplines, highlighting single exhibitions as well as the most stunning collections and treasures of our cultural heritage.

Slow Art Day: Tell us more about how you ‘see’ art.

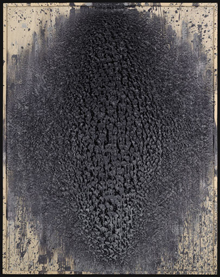

Elizabeth: The first encounter with art is a visual one – you just need your eyes for discovering and experiencing its richness and plurality. A certain knowledge or expertise is what comes in a second or even third step. ikono offers this very first meeting: we are building a visual bridge to the arts, encouraging you to trust your eyes, and to rely on what you see and feel.

Slow Art Day: How does this connect with your notion of time?

Elizabeth: We take the notion of time seriously by inviting you to dive into the artwork contemplatively and to become fascinated by its details. You will always discover things you have never seen or noticed before! We allow art to speak for itself, which is why we never add any sounds or narrative elements and why we avoid any interruptions from commentary or advertisement. However, in case you would like to know more, you can of course find all additional information and further links on our homepage.

Slow Art Day: You guys are planning something special for Slow Art Day – five video clips, each dedicated to a single artwork. Say more.

Elizabeth: We decided to dedicate the entire program for April 27th, 2013 to Slow Art Day. Our curators have selected some of our most beautiful video clips to be presented throughout the day: we will showcase Hans Holbein the Younger’s double portrait of The Ambassadors and the unexcelled depiction of The Tower of Babel, painted by Pieter Brueghel the Elder. We will present artworks of Caspar David Friedrich, the wonderful Eugene Delacroix, Vincent van Gogh, and the universal genius Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Viewers will also find contemporary examples, including the fascinating light installation of Kite & Laslett, our current Artists of the Month, and the Spatial Reflections series, a selection of artistic positions from Lebanon, Syria and Palestine, curated by Charlotte Bank. I do not want to reveal too much before its presentation, so please feel cordially invited to tune in for discovering more!

Slow Art Day: Can people watch ikonoTV if they are not currently in your cable footprint?

Elizabeth: At the moment you must meet certain technical requirements to watch our HDTV program. While ikonoMENASA is broadcasted in the countries of the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Southern Asia via satellite (ArabSat) or IPTV (du, Etisalat or Solidere IPTV Broadband Network), ikonoTV is on view in Germany and Italy via Telekom Entertain and Cubovision.

But we have very good news: In 2013 we will increase our international presence by also being on view in new countries throughout Europe. Furthermore, we have already started preparing our live web stream, which is to be launched within the upcoming months. From that very moment on, everyone around the world will be able to enjoy art and to contemplate it wherever they are-an amazing perspective! In June we will announce further details, so stop by our website or join our newsletter to stay posted. Also begin checking our blog right away, where you will find all further information about ikono’s support of Slow Art Day 2013!

Slow Art Day: Great – thanks for sponsoring Slow Art Day again this year.

[Make sure to tune into ikonoTV, Berlin, if you can!]