From time to time, we post short articles from Slow Art Day hosts. The article below is by veteran Slow Art Day host, Paul Langton.

A rainy day. I am early for an appointment. An opportunity to go to a gallery for forty or fifty minutes, without expectations? I realise don’t actually know what is currently on at the gallery.

Fortunately I listen to my intuitive self, and a few moments later find myself in the Whitechapel Gallery, exploring Mel Bochner’s fascinating work. But, I become aware that his exhibition would need more time than I feel I can allow. I then go into a room with a single sculpture. A tree. Immediately fascinated I walk around the sculpture. I notice the materials used – gold leaf, bronze. I feel at home in the space and decide to spend some time in this room.

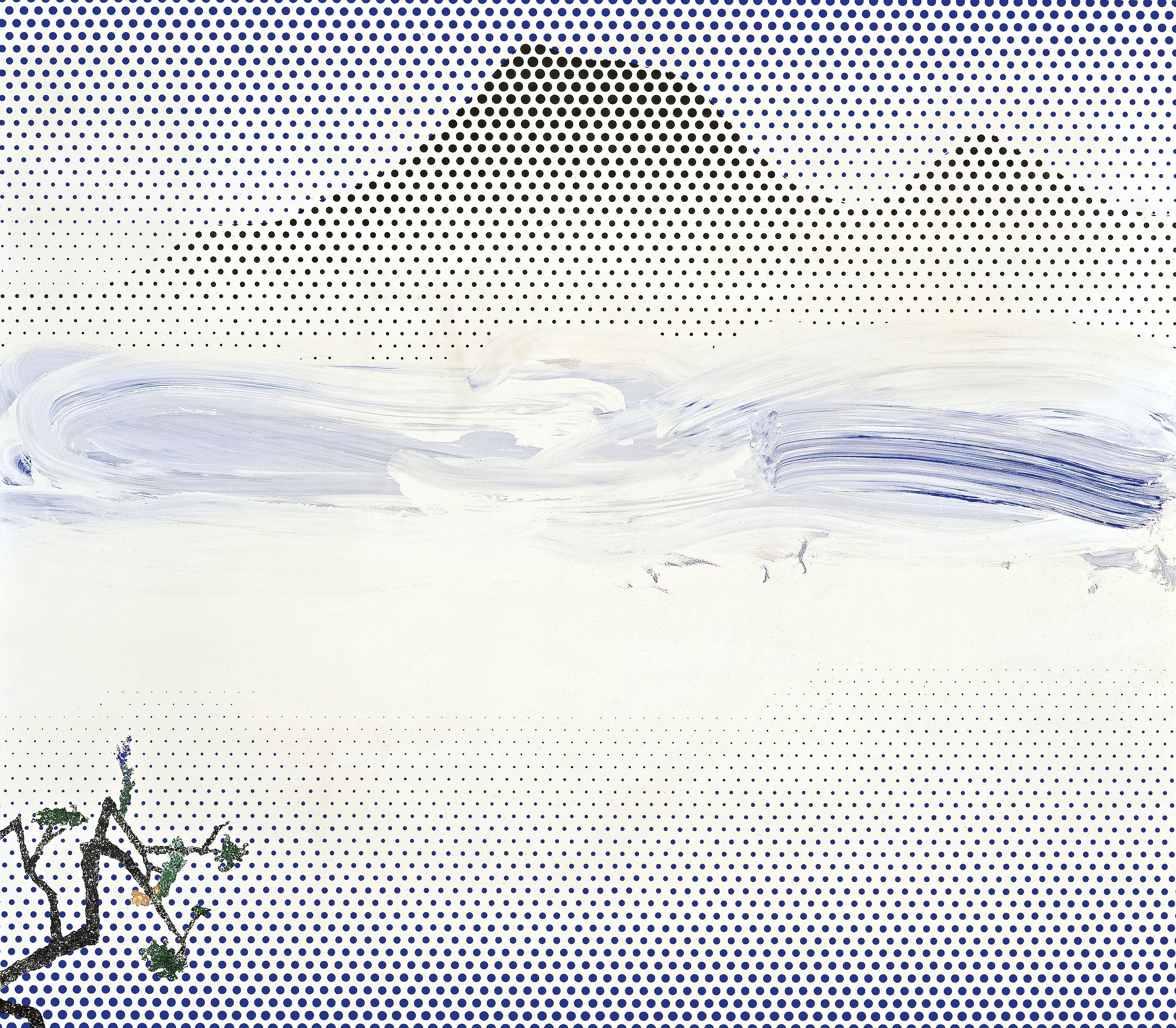

Spazio di Luce by Giuseppe Penone at the Whitechapel Gallery (image from the Whitechapel Gallery website – click the image to visit)

A well-placed bench allows for some slow art thinking. Who is this by? What is it doing here? I walk around, I sit down. I walk around again. I go and read the information about the sculpture. I ask the attendant if I can I touch it.

The exhibition is very peaceful. Occasionally people come in and I notice their reactions to the piece, yet I am pre-occupied by my own thoughts. I feel I am in the right place at the right time, as though I was meant to see this piece today. I love the way each time I view the tree it look different and I love the light further illuminating the gold leaf, shining light on this wintry day. I walk alongside it and see it from different angles. I don’t hug but I do touch.

The sculpture, I find out, is Spazio di Luce (Space of Light) by the Italian artist Giuseppe Penone and is a Bloomberg Commission, in the Whitechpael Gallery until September 2013. Space and light, they seem ideal words. It’s good to find out it will be here for a few months, and another visit will be possible. I realise I may have seen some of Penone’s work before as part of Arte Povera at Tate Modern, but I couldn’t be specific.

I have been thinking of trees in the last few weeks and the importance of trees – there was a fascinating discussion on the radio the previous month about trees with James Aldred and Mark Tully – and this sculpture adds an extra dimension to my current feelings and thoughts. I reflect on nature, art, myself, others, and art as part of life.

The light in the title becomes so appropriate as I leave the gallery, literally feeling lightened and uplifted. I then wonder on how something so beautiful and fascinating just appeared in my day without notice. In my head I thank the artist and the gallery, for being presented with and for being present, for some time, with this wonderful sculpture. Please visit if you can.

(If you are not able to visit a video of the artist talking about the work is on line: http://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/the-bloomberg-commission-giuseppe-penone-spazio-di-luce).

The Whitechapel Gallery is one of 160+ Slow Art Day venues for 2013. Click here to find out more or register.

– Paul Langton

Note: An earlier version of this piece first appeared in Paul’s blog: http://artsandmoresw4.wordpress.com