When we walk into a museum or gallery nowadays, we are instantly confronted with a rather large number of artifacts which demand our attention. I always find myself pondering where to start my journey. Is it with this painting to my left? How about this wonderful African mask straight ahead? While museums and galleries are generally quiet and peaceful places, they nevertheless hold enough artifacts to potentially overwhelm the visitor.

It’s true that we don’t spend enough time actually looking at a painting anymore. In fact, we spend more time reading the description underneath it than contemplating the painting itself. Even though we attempt to return to contemplation with the help of Slow Art Day, there is nevertheless a crucial element in today’s paintings that is not always beneficial to slow looking.

When we stand in front of a painting, the whole scenery is present before us. It’s not entirely surprising that we spend little time on contemplating paintings. We think that because everything is there in laid out in front of us at one time, we don’t have to work very hard at the act of looking. It’s certainly beneficial to those always-in-haste people that today paintings are not unrolled and displayed gradually, as traditional Chinese scroll paintings were.

Hanging scrolls and hand scrolls were common features in Chinese painting, which often featured beautiful landscapes – mountains and waterfalls in particular. Painters infused their works with Taoist thoughts and beliefs such as simplicity, which was, in part, made visible in the use of monochrome textures, i.e. black and white. It finds its most extreme application in Zen painting; works famous for their black ink on white rice paper.

The often meters-long scrolls had two main goals. First was the delayed contemplation. The viewer was unable to quickly grasp the entire scenery, because the scroll had been unrolled scene after scene, so that the viewing process lasted longer than we spend on paintings (even during Slow Art Day!). And then there was the narrative aspect, the ancient precursor of film if you will, long before photography paved the way for the development of cinema. The step-by-step unraveling of the scroll allowed for a narrative development. It thus contained not only one scenery, but several, which were linked to one another and formed a painterly entertainment for the viewers. It was a slow pleasure, in a way like a slow film, which takes its time to develop.

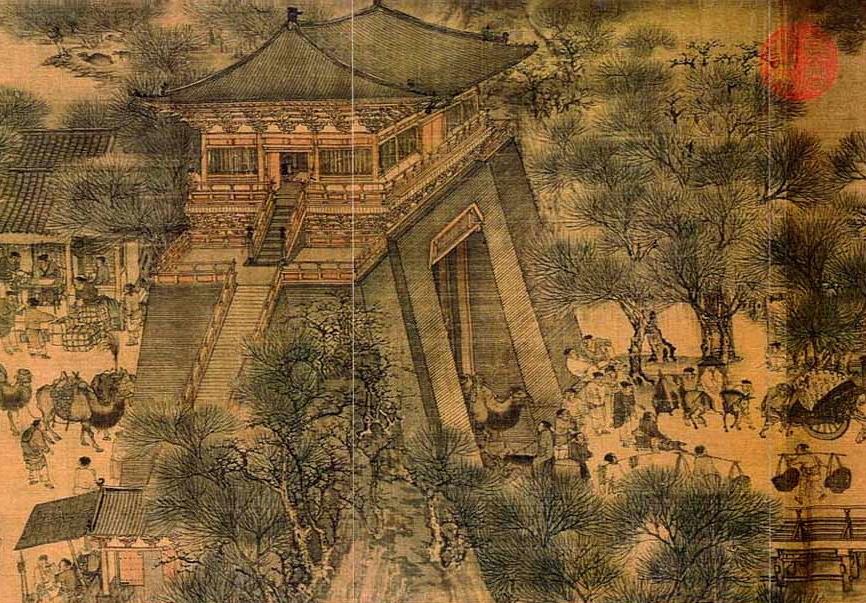

The above painting is a five metre long scroll from the Chinese Sung Dynasty (c. 960-1126), painted by Chang Tse-Twan. It is considered as a scroll painting that stands at the beginning of narrative development in Chinese painting. While nowadays we would see the entire scroll displayed at once, in those days viewers only saw parts of it, one after the other. It is not difficult to see how the slow unrolling of the scroll created a heightened pleasure for the audience. I often wish that painters would return to this form of painting that not only creates a work of quietness, but also generates excitement over what we will see next in the scroll; a real journey through a painting.

– Nadin