Slow Art Day has asked its 2013 college interns to write short summaries of their own experiences looking slowly at artworks of their choosing.

Few paintings possess the same level of fame as Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. Who was the enigmatic girl in the painting? What was her relationship to the artist? Why did he paint her wearing such a large and distinctive pearl earring? Art historians have speculated tirelessly on the answers to the questions, and the level of mystery surrounding the Girl has led her to be labelled “the Dutch Mona Lisa.”

Given all this, it’s next to impossible to not be aware of Girl with a Pearl Earring. The last time I did a slow art viewing experiment, with Jay DeFeo’s piece The Rose, I had only a passing familiarity with DeFeo and her work. But Girl is an inescapable piece, so when I viewed the painting at the de Young Museum’s special exhibition Girl with a Pearl Earring: Dutch Paintings from the Mauritshuis, it turned out be a completely different viewing experience.

Girl is obviously the star of the exhibition. She appears on all of the de Young’s promotional material for the exhibition, and her face is currently plastered on the side of every bus in San Francisco. Before I even walked into the exhibition I’d seen her face many times over the past few weeks, and was, frankly, a little sick of her. But as any art lover will tell you, seeing a reproduction of a work pales in comparison to seeing the work in person.

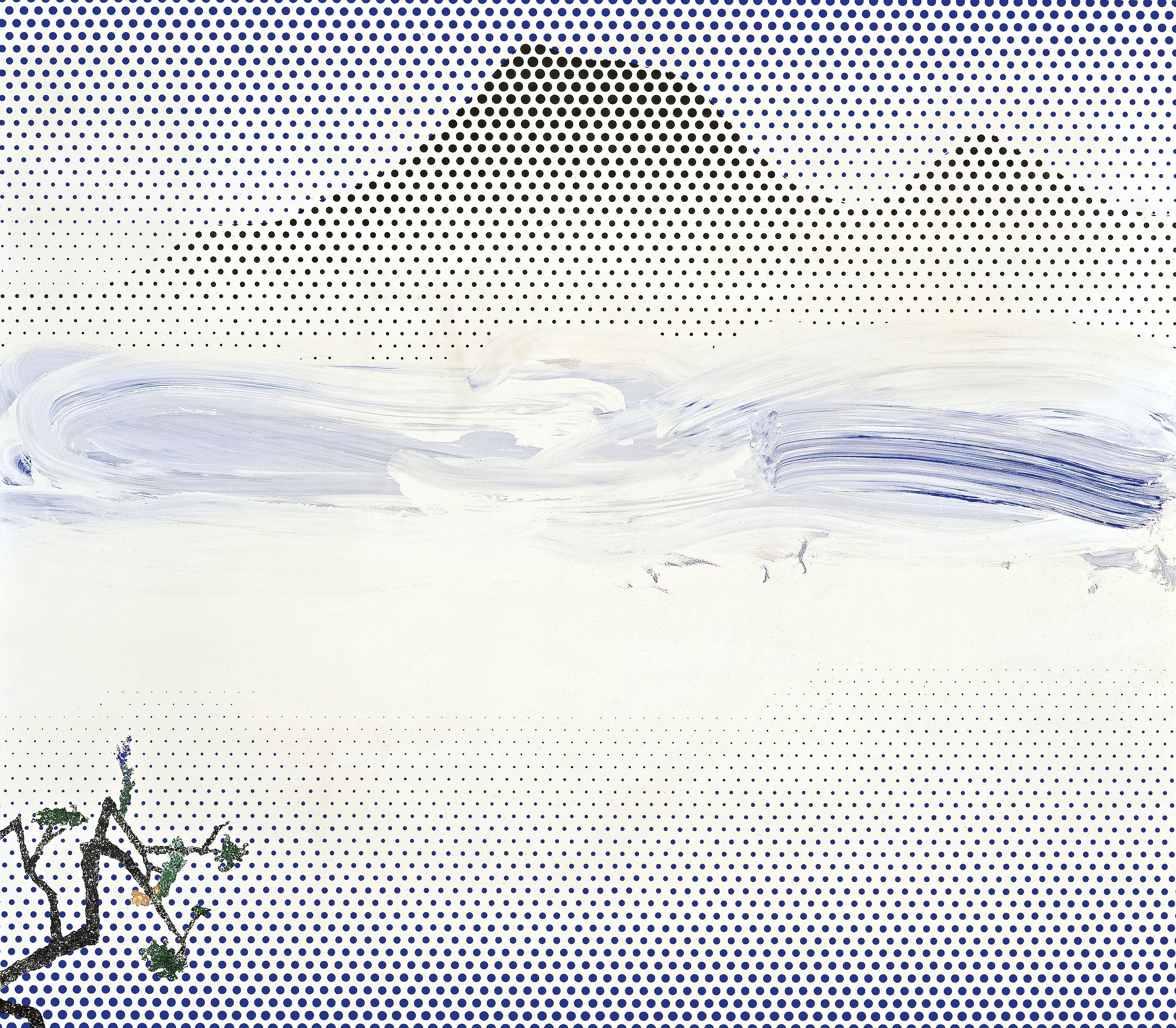

Jan Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring (detail), 1665. Image courtesy of the de Young Museum.

The painting’s placement in the exhibition reinforces its central importance. The exhibition spans five rooms of the gallery, all of which are densely packed with paintings, with the notable exception being the room that houses Girl with a Pearl Earring. The room’s only occupant, the Girl confronts you head-on, visible even from the preceding gallery. The painting’s dimensions are rather underwhelming in person, something that the curators and installers cleverly disguised by shining bright lights on the painting and shrouding the rest of the room in darkness. An otherworldly glow seems to emanate the canvas.

When conducting slow art viewings, I like to view the artwork from as many different angles as possible – far away, up close, from the sides. However, I quickly discovered that this is difficult with a painting as diminutive as Girl with a Pearl Earring. I could barely see it when trying to view it from across the gallery; I just got an impression of large blocks of bright colors, an impression that was validated when I moved closer. One of the things that struck me was how sparingly Vermeer used different shades of pigment. Although the painting seems rich in color, and it certainly is, relatively few different shades of color are used in the painting. It seems almost minimalistic – although this isn’t something we generally associate with the Dutch Golden Age, I was reminded of the sparsity of different color shades used in abstract paintings by Mondrian or Rothko.

However, after spending several minutes in front of the piece, I did start to notice several subtle but startling uses of color. There is a small dot of white paint at the corner of the Girl’s mouth that echoes the white dots in her pupils. Her lips appear at first glance to have been painted bright red, but upon closer examination actually contain traces of black, gray, white, and even blue pigment. Even though her pearl earring is the painting’s brightest focal point, it is actually painted almost entirely in black and gray, with just one small white brushstroke that lends it a luminous, glowing quality amidst the darkness of the surrounding canvas.

I realized at the end of my slow viewing experience that the work, which seemed so diminutive at first glance, seemed to have taken on greater proportions. After looking at each individual detail of the painting at great length, the whole of the painting had become much larger than the sum of its parts. The work is only one and a half feet high, but it feels monumental and, at the same time, intimate, as if she is looking at you alone. If you are in San Francisco, I highly recommend that you make the effort to go see this painting (and the rest of the exhibition). You may think you’ve seen it already, on postcards, book covers, and other reproductions, but when you see it in person you will realize that until that moment you’ve been mistaken.

– Maggie Freeman, Mills College

Jan Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (ca. 1665) was viewed at the special exhibition Girl with a Pearl Earring: Dutch Paintings from the Mauritshuis at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, CA]